Developing Trails That Become a Natural Part of the Landscape

At Professional Trail Builders, our team has been creating motorized and nonmotorized recreational trails for more than 10 years. We strive to provide our clients in Ontario with high-quality services to help take them to new and exciting places in the wilderness.

Building Pathways to Nature

Our group ensures that the paths we create follow principles of geometry, hydrology, and soil science. We work hard to develop fun tracks that fit into the landscape to achieve our goal of bringing people and the natural world together.

Promoting Sustainability

Most of the time in our site visits, we notice many existing trails have eroded due to poor design or lack of maintenance. To avoid this scenario, we build sustainable trails. These have constant flow and roll that minimize long straight sections and grade reversals that force water off the tracks regularly.

Five Essential Elements of Sustainable Trails

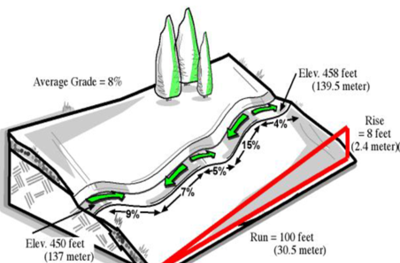

A trail grade should not exceed half the grade of the side slope the trail is traversing. If the trail’s grade exceeds half the slope’s grade, it’s considered a fall-line trail. Water will be focused to travel the fall line, the path of least resistance, rather than flowing across it.

Using a clinometer to measure the side slope percent of grade, we will keep the average trail tread grade below half of what is measured to ensure good drainage. For example, with a side slope of 20%, the trail’s tread will not exceed 10%. Note that slopes exceeding the half rule for short sections (roll) will be fine provided there are ample drainage and good soil.

The half rule is often more important in areas of gentle, erosion can still occur and the half rule still applies. Flats and low lying areas will be avoided, as trails built in these areas are more likely to collect and hold water.

Generally, a 10% average grade is quite sustainable. The final trail will often undulate, creating areas that have short sections steeper than 5% but no greater than 8% wherever possible.

Maximum grade, usually around 15% to 20%, is the steepest allowable grade based on several site-specific factors, which include: Half Rule (the trail’s grade is less than half the side slope grade); Soil Types (some soils support steeper grades than others); Rock (solid rock or rock-embedded slopes can be steeper); Annual Rainfall (heavy rainfall leads to water-caused erosion, low rain leads to dry loose soils); Grade Reversals (a short dip followed by a rise forces the water to drain off the trail); Types of Users (low-impact users, hiking and biking, can sustain a steep grade. While higher-impact users, horses and motorized should have lower maximum grades); Number of Users (higher anticipated use leads to lower grades); Difficulty Level (trails with a higher degree of technical challenge tend to have steeper grades—grade reversals and tread hardening is sometimes necessary to ensure sustainability).

A grade reversal is a spot at which a climbing trail levels out for a few metres before rising again. This change in grade allows water to exit the trail tread at the low point of the grade reversal. Grade reversals are also known as grade dips, grade brakes, drainage dips, and rolling dips.

Grade reversals also make a trail more enjoyable. On long downhill sections, grade reversals slow speeds and add variety and challenge. On uphills, brief descents help users regain their momentum.

As the trail contours across a hillside, the downhill side, or outer edge of the trail’s tread will be slightly lower than the uphill side, or inside edge by 2 to 5 percent. Outslopes encourage water to sheet across the trail rather than travelling down the trail’s center.

Get in Touch

Contact us today for any questions or concerns about what we do.

25' span x 8' width

25' span x 8' width